Tug On The Ringelmann Effect To Start Acing Your Productivity

Last update: 3 August 2023 at 11:58 am

A man named MaxRingelmann observed something unusual in people around 1913. Ringelmann, a French agricultural engineer, grabbed a rope and had people tug on it individually.

Then he invited a group of those same folks to tug on the rope. He noticed that when people pulled in a group, they exerted less effort than when they pulled alone.

This is also known as the Ringelmann effect, or social loafing.

It refers to the fact that as the size of a group grows, individual output tends to decline. And it isn’t limited to tug-of-war games: more than a century after Ringelmann‘s discovery, it can be found in businesses like Google and Facebook.

There’s a good possibility it’s occurring at your place of work as well.

Definition Of Ringelmann Effect

The Ringelmann effect describes how as a group grows in size, it becomes less productive in terms of production per member.

Max Ringelmann (1861–1931), a French agricultural engineer who investigated the productivity of horses, oxen, men, and machinery in diverse agricultural applications, was the inspiration for the effect.

He discovered that while groups frequently outperform individuals, the addition of each additional member to a group results in a smaller increase in output.

Following research has shown that the loss of production is driven by a decrease in group motivation (social loafing) and the inefficiency of bigger groupings.

Cause Of The Ringelmann Effect

Groups struggle to attain their full potential, according to Ringelmann, since numerous interpersonal processes subtract from the group’s overall proficiency.

Two different processes have been recognized as potential drivers of lower group productivity:

motivation loss and coordination issues

Motivational Decline

Motivation loss, also known as social loafing (and not to be confused with a burnout), is a drop in exerted individual effort found when people operate in groups rather than alone.

According to Ringelmann, group members tend to rely on their coworkers or co-members to put in the needed effort for a common duty.

Even though most group members feel they are contributing to their full capacity when questioned, research suggests that they are loafing even when they are ignorant of it.

The following is a list of some of these options:

Increase identifiability: People are more motivated to put out more effort into a collective work when they believe their individual thoughts or outputs are recognizable (e.g., subject to review).

This is because when a job is easy and individualistic, individuals are anxious about being judged by others (evaluation anxiety), which increases productivity through social facilitation.

Similarly, if a team task allows group members to remain anonymous (that is, to remain in the background of group interactions and contribute in non-salient ways), they would feel less pressured about being judged by others, resulting in social loafing and lower productivity on the group task.

Reduce free-riding: People who engage in social loafing often fail to contribute to the standard because they assume others will compensate for their weaker team members. As a result, individual members should be made to feel as though they are an essential part of the team.

Members are more likely to work harder to achieve collective goals if they believe their own responsibilities within the group to be more important.

A comparable impact may be accomplished by shrinking the group size since as the group size reduces, each member’s function becomes increasingly important, decreasing the potential to loaf.

The increased effort of group members’ engagement in the work or goal at hand: Another way to decrease social loafing is to simply increase group members’ involvement in the activity or goal at hand.

This can be accomplished by turning the job into a friendly competition among group members or by attaching incentives or punishments to the task based on the group’s overall performance.

In a similar line, social compensation may be used to discourage loafing by persuading individual group members that the objective at hand is essential but that their colleagues are uninspired to achieve it.

Coordination Problems

Individuals’ performance in groups depends on their own effort (e.g., abilities, skills, and effort) and the different interpersonal dynamics at work inside the group.

Even if group members have the skills and knowledge needed to perform a task, they may not be able to effectively coordinate their efforts.

Hockey fans, for example, may believe that a certain club has the highest chance of winning merely because it is made up of all-star players. In fact, if a team member cannot properly coordinate their activities during gameplay, the team’s overall performance would most certainly suffer.

Coordination issues among people’s efforts quickly diminish, according to Steiner (1972), are caused by the demands of the tasks to be completed.

If a task is unitary (i.e., cannot be broken down into subtasks for individual members), requires output maximization (i.e., a high rate of production quantity), and requires individual motivation among members to produce a group product, a group’s potential performance is dependent on its members’ ability to coordinate with one another.

Why are Small Teams Strategically Beneficial?

Entropy, which occurs in teams as a result of unchecked rapid development, not only stymies progress but also generates disorder and confusion. If left unchecked, it can cause major holes in a team’s foundation.

It can be combated in a variety of ways. One of the simplest is to deal with squad composition. The Ringelmann Effect refers to the fact that as the size of a team grows, team members become less productive.

Scrum, too, promotes a small team as a success tenet.

This is due to the fact that small design or engineering teams have a considerable advantage in the four essential qualities listed below.

Alignment

The larger the team, the more difficult it is to achieve alignment. And a lack of alignment makes it more difficult to make a strong impression.

It is comparatively easy to achieve alignment in a small group. The explanation for this is simple: the larger the group, the more work it takes to nudge them in the correct direction.

Slightly fewer members are, the easier the coaching team towards the north star.

Communication

The larger the team size, the greater the communication effort required for optimal collaboration. Even Scrum routines like daily standups and retrospectives take longer as the team becomes larger.

(It’s no wonder that Scrum recommends keeping teams to a maximum of seven people.) As a result, as the team grows larger, more time is spent communicating, leaving less time for development and poor communication that may lead to team managers having to engage in issue management to avoid a crisis.

Cohesiveness

The tighter the team is linked to each other, the smaller it is. As the team grows in size, the distance between the electrons, or individuals, and the team’s nucleus begins to grow.

Some of these electrons may get free and move to another atom’s outermost orbit (another team or another company).

On the other hand, people in small teams are more closely connected to one another since they spend so much time together, eliminating social loafing. It’s easier to get to know one another, ask for support, and exchange ideas when there are fewer individuals on a team.

It also aids in the formation of strong relationships that propel the team to victory.

The Ringelmann Effect – Background and History

Max Ringelmann was fascinated by different elements of agricultural efficiency. He was mainly concerned with the factors that make draught animals like horses and oxen and men more or less efficient at their jobs.

Ringelmann‘s study is among the first systematic social psychology studies. His study reflects some of the oldest known human factors research, as he was also interested in the process by which animals and men may be more efficient.

In reality, at the time of his original research, the human factors element of his research was the major emphasis. In contrast, individual and group performance comparisons were just a secondary concern.

Ringelmann used male volunteers to pull horizontally on a rope for around 5 seconds in some of his preliminary studies. Participants tugged on a rope alone, in groups of seven, or in groups of fourteen. During this time, a dynamometer was utilized to record their maximum pulling effort (a device that measures the maximum force exerted).

The average force applied by those who pulled alone was 85.3 kg per individual. The mean force exerted per person was 65.0 kg and 61.4 kg, respectively, when participants pulled in 7- and 14-person groups.

As a result, as the size of the group grew larger, the average force exerted per member dropped. Ringelmann reported similar effects when participants were asked to push a crossbar attached to a two-wheeled cart. Participants exerted higher force (170.8 kg) when they pushed alone than when they pushed jointly with another person (154.1 kg).

A Curevilinear Relatinoship

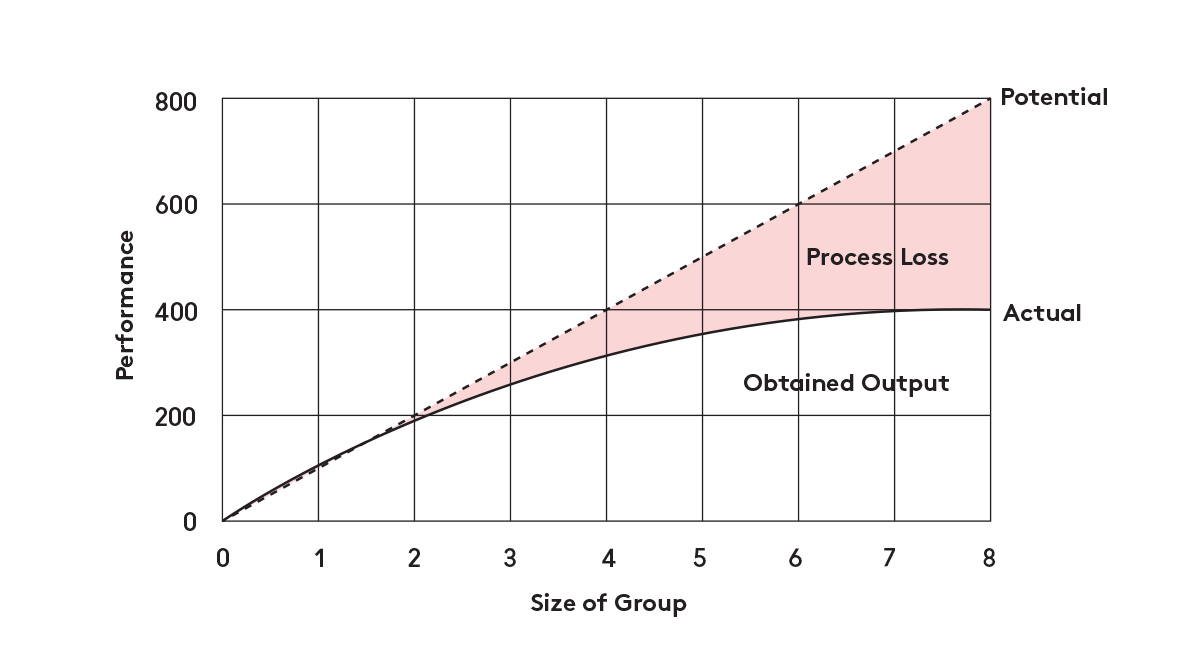

One of Ringelmann‘s most well-known discoveries is his study of relative group performance as a function of group size in groups ranging from one to eight members. The individual effort was reduced as a function of group size, according to his prior studies.

For example, if one worker’s total force was 1.00, the force exerted by two through eight employees was 1.86, 2.55, 3.08, 3.50, 3.78, 3.92, and 3.92, demonstrating a curvilinear relationship between group size and group performance.

That is, the overall force exerted by the group dropped as group size grew, but the difference between two and three-person groups was higher than the difference between four and five-person groups, and the difference between seven and eight-person groups was still smaller.

Ringelmann did not indicate what sorts of jobs these statistics were based on, which is interesting. They may or may not have come from rope-pulling-specific research, as is commonly thought.

He identified two possible causes for this drop in individual performance when working in groups. The first was the result of a lack of coordination. Two individuals tugging on a rope, for example, would be more coordinated (and hence more likely to be in sync) than a group of seven or eight people pulling together.

This, according to Ringelmann, was the most plausible explanation. Nonetheless, he admitted that such an impact might be the result of a drop in drive.

Summing Up the Ringelmann Effect

That’s fantastic, but how can we combat the Ringelmann effect on a personal level? How can we prevent it from happening in the first place?

It’s actually rather simple; no social science knowledge is necessary. Simply put, ask yourself, “How can I be of service?”

If you’re in charge, it’s a good idea to divide your large staff into smaller pods. It’s simpler to develop common meaning and assist everyone in understanding their group effort with smaller pods. Then devise rituals for these pods to engage with one another and see whether they are all marching in the same direction, such as a scrum among scrums. Then, despite your rising size, you should be able to fulfill your goal for success.